Confronting climate disclosure: Why financial institutions are struggling to remain accountable to their net-zero goals

With emissions reporting being mandated for all Singapore-listed companies from 2025, it is critical to understand the complexities of the climate disclosure and management. PSYKHE partnered with a climate technology startup to uncover the challenges faced by financial institutions as they strive towards their net-zero goals.

Written by Juliette Khoo

Executive summary

Sustainability. Net-zero. Climate-aware. Planet-friendly.

You might not realise it, but the financial industry is a key driver of decarbonisation across all sectors, supply chains and geographies. For example, they provide the funds for new coal plants to be built.

In the financial world, there has been a seismic shift towards tackling the big Cs: climate, carbon, and commitment. This has largely been driven by the tightening of regulations on climate finance disclosure all over the globe. In Asia, Singapore will be one of the first countries that requires mandatory climate disclosures for all listed companies by FY2025 and mandatory Scope 3 GHG (Greenhouse Gas) emissions reporting by FY2026.

But as we inch closer to 2050, some of these organisations are beginning to default on their net-zero commitments. A study by KPMG in 2021 benchmarking 35 major banks globally revealed that for every 4 banks who commit to reducing financed emissions by 2050, only 1 of them discloses quantitative details of their financed emissions.

This fact speaks to a great challenge that many financial institutions (FIs) face in climate accountability. The bulk of FI's carbon emissions come from either bank loans or investments made by fund managers. These indirect, downstream GHG emissions occur as a result of distributing financial products.

Calculating baseline emissions is only the tip of the iceberg. FIs with a higher maturity have also deployed extensive resources into risk management and climate strategy. The challenge is making emissions data trickle down into the subsequent layers of climate management that sit underneath.

In many larger FIs, these strategies are handled by different teams, creating silos. Resources are not optimally allocated towards streamlining data collection, stalling the implementation of further initiatives down the line that will accelerate transition finance.

To identify the specific problems FIs have to overcome, PSYKHE, a user-centred research and design agency, partnered with a startup that offers enterprise carbon reporting software. Together, we conducted in-depth interviews with climate and sustainability experts in the financial industry to find out more about their pain points in calculating and managing financed emissions.

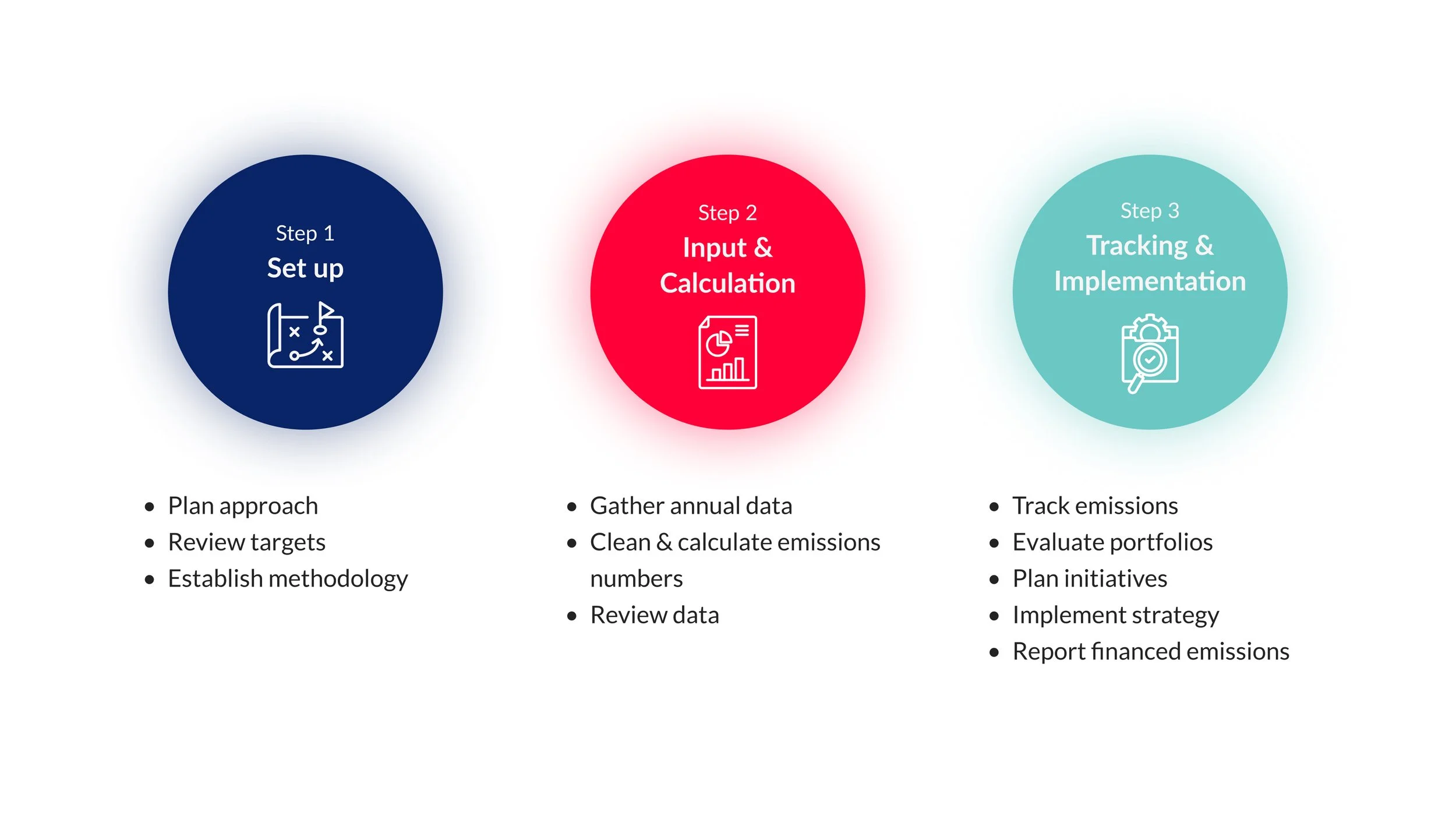

A laborious data collection and calculation process

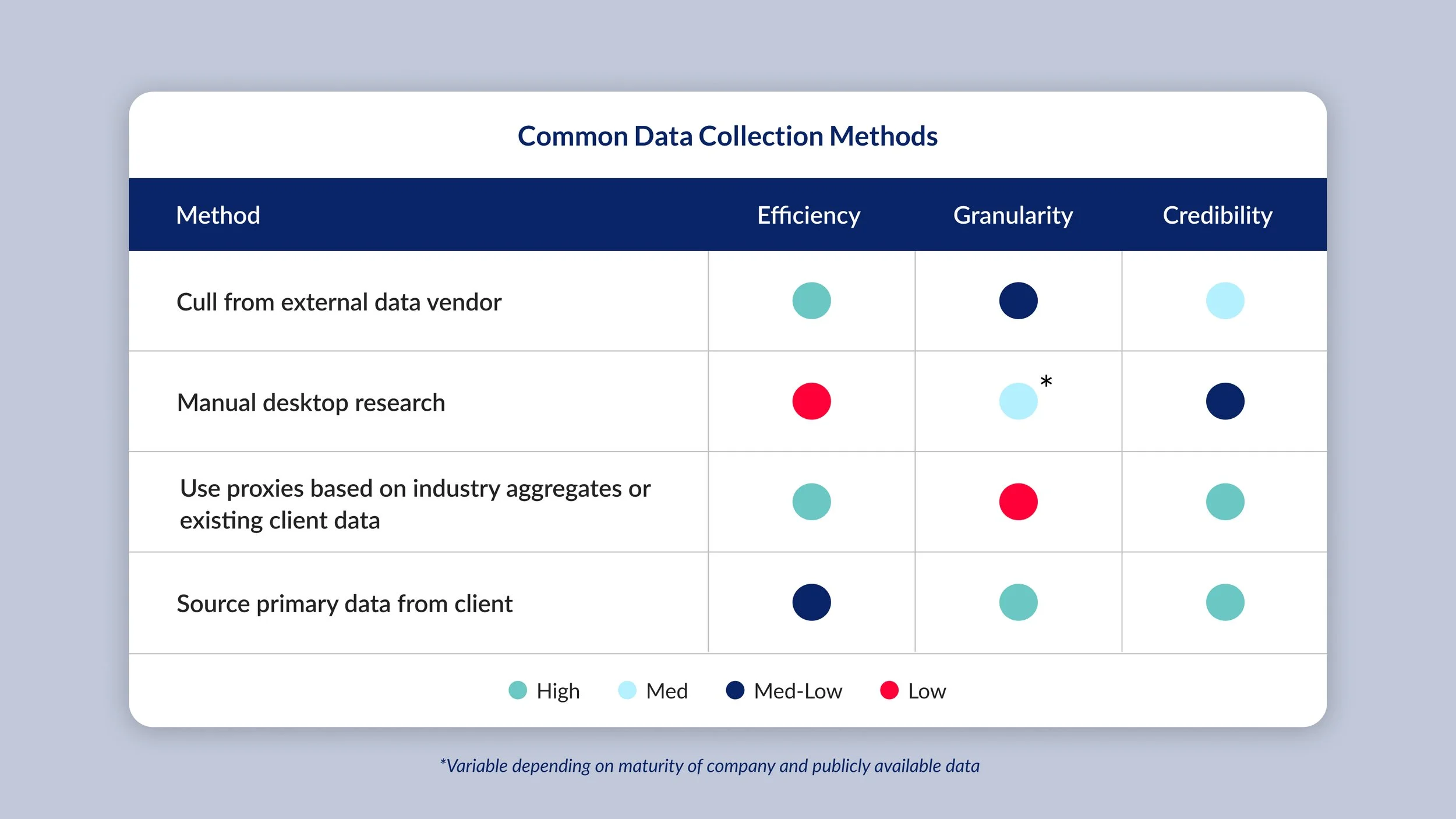

At present, data collection is lengthy and convoluted, with organisations struggling to reconcile the data points from different sources. Since there is no single centralised database for carbon emissions in Singapore, data is first culled from external vendors. When emissions data isn’t readily available, especially for non-listed companies and SMEs, manual desktop research is needed.

An interviewee from a major regional bank revealed:

“Finding emissions of every borrower can be tedious and manual. For 1 sector, the team has to go into desktop research for 500 customers.”

The next option they usually resort to is proxies (e.g. tCO2e/€M, or emission factors for the sector per unit of revenue) as public aggregated data may be readily available depending on the sector. Companies also use existing client data to create a proxy for those who don’t measure emissions.

“Using proxies is quite [a] sector specific application right now. We don’t use a global industry average, but we do identify similar client profiles to use as a proxy.”

The final resort is to reach out to the client directly, which is a method that interviewees felt was high effort and had a low chance of success. One interviewee shared that clients are unlikely to provide confidential data on a standalone basis to their creditors.

FIs generally strive for efficiency in their annual data collection exercises. However, when dealing with many different sources of data, FIs need to consider more than just the efficiency of the data collection method. We found out that the integrity and granularity of the data are also key determining factors of the chosen method. This is due to two main reasons.

Firstly, even if the data is available, the data source and collection method might not be credible. For example, since SMEs generally don’t report emissions data, it’s only natural to want to verify or cross-check the numbers that a client has given.

Secondly, the use of proxies means that the value is an estimate based on certain assumptions or dependencies that are not spelt out. Combining values from a specific client with industry averages ultimately makes emissions tracking less accurate, which may result in a misinformed climate strategy.

One of our interviewees, a net zero team lead at a global bank in Singapore, said:

“Understanding the client model becomes so critical because applying a proxy needs to be very innovative in this space. A lot of regulators are very keen in [sic] what portion of your measurement or risk identification is based on proxies”

To develop a more transparent, standardised method of reporting GHG emissions associated with financed emissions, the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) established the Global GHG Accounting and Reporting Standard for the Financial Industry in 2019. Emissions are split into 7 different asset classes, each with a separate data quality scorecard that helps institutions declare the reliability of their reported emissions.

An ambiguous climate strategy

After calculating baseline emissions, FIs will seek to use this data to refine their climate risk assessment methodology. If they are able to identify specific drivers of change in emissions, immediate action can be taken to reduce the risk of increasing their year-on-year emissions. The tricky part is translating emissions data into these quantifiable risk indicators that can be tracked year-on-year so that a robust climate strategy can be formed.

Climate and reputational risk is also dependent on the natural and political environments the business resides in, which must be accounted for in the methodology. However, the biggest hurdle the sustainability team has to overcome is an interpersonal one: providing both internal and external stakeholders with a convincing business case.

“[The implementation of an] ESG risk assessment had huge pushback -RMs didn’t want to spend time doing it but eventually accepted it because of [the] push by [the] senior management.”

It takes time for new ideas to go through a period of admonishment, acceptance, and finally, adjustment. The frontline managers are the enablers of client engagement. Getting them invested in the strategy is crucial to changing the carbon footprint of each portfolio.

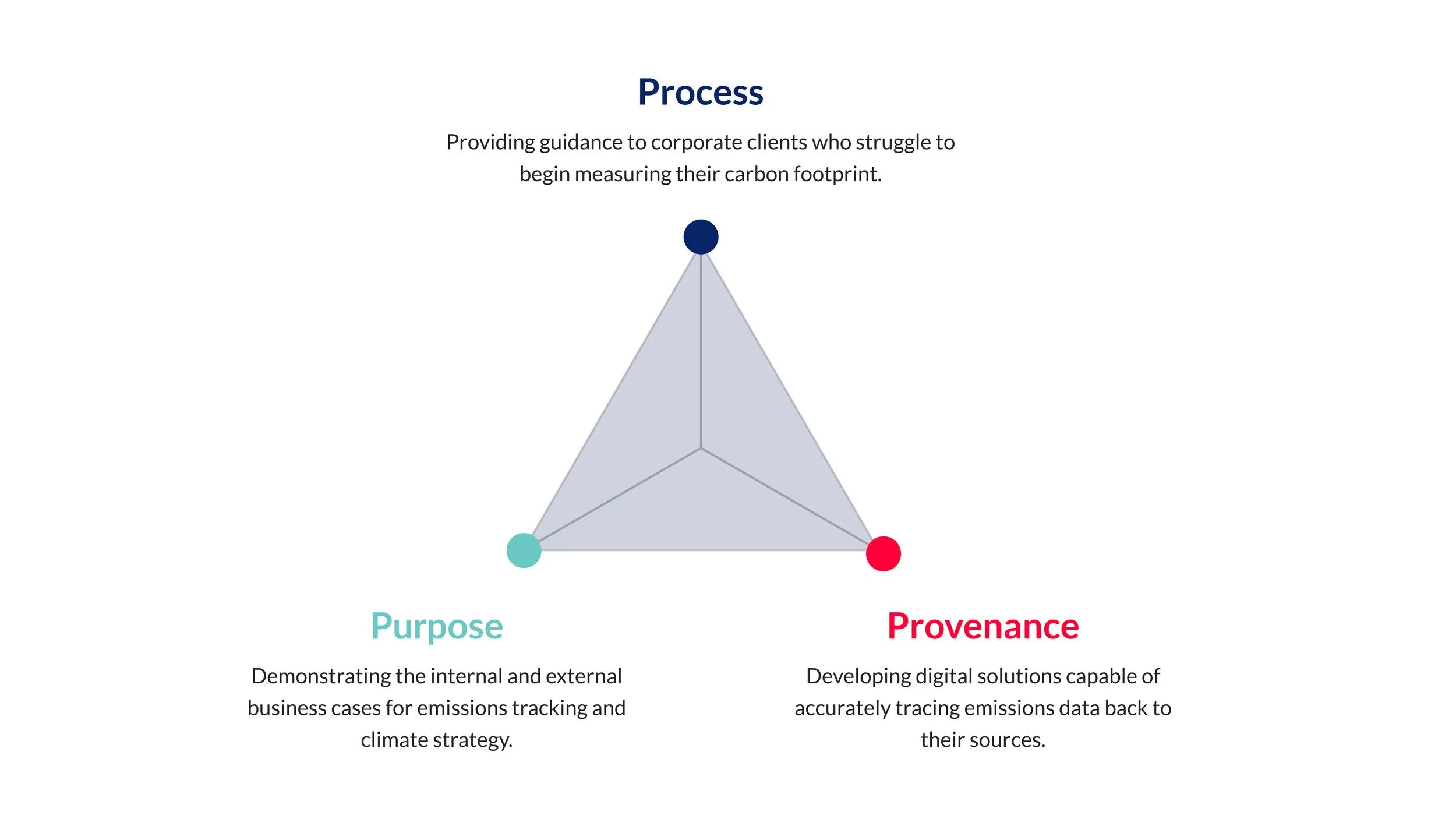

Based on the primary research conducted and several brainstorming sessions of our own, we defined three key focus areas that FIs should focus on to streamline their net-zero transition pathways. Our recommendations are centred around three Ps: Purpose, Process and Provenance.

Demonstrating the purpose of climate tracking and strategy to internal and external agents

Some interviewees pointed out that educating corporate clients on data collection is insufficient:

“We have tried calls, peer analysis, peer reports, trying to show them the power of the data, trying to tell them, you know, this is what all financial institutions are looking at.”

Helping to define purpose will not only help streamline the data collection process but also refine the climate action plan by identifying clients and industries that present a transition risk. In the long run, this helps the organisation meet year-on-year emissions goals by shifting their portfolios to focus on sustainable finance or climate-conscious borrowers.

We focused on two ideas that tie climate strategy back to stakeholders’ objectives:

Firstly, developing scenario modelling tools that can help forecast risk:

Presently, general data visualisation tools such as Tableau and Power BI lack the capabilities to quantify physical and transition risk based on standard financial institutions, geographical, and sector-specific events. Industry-specific tools will need to be developed for this capability. Providing a strong business case to stakeholders sets the stage for them to make informed, data-driven decisions on climate strategy using these platforms.

Additionally, forecasting changes in portfolio returns based on climate-focused indicators and events allows risk management and industry teams to decide on the optimal allocation of assets in the case of a black swan event.

Secondly, building use cases through projection tools:

One interviewee, a Net-Zero Sustainable Finance Director, expressed that the biggest challenge in the whole process is gaining internal buy-in from frontline managers:

“[The] most significant pushback, that you get, principally, is this is not real, this is all hypothetical. It’s not impacting me today. It’s not impacting me yet.”

Several banks that are leading in the sustainability space are already developing in-house projection tools.

For relationship managers (RMs), the projection of their portfolio’s long-term glide path is a more tangible and relevant tool that will help them forecast the return on assets in light of any precedented transition risks or physical risks.

This projection tool can also be used on a client level to convince them of the need to buy into sustainable finance as part of accelerating their transition plans and helps clients establish a business case for measuring direct emissions.

Seek to educate clients on the process of measuring their direct emissions

An over-use of proxies makes emissions calculations imprecise, which is why the Global GHG Accounting and Reporting Standard for the Financial Industry requires a mandatory declaration of proxy values that have been used in the calculation under the Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Accounting and Reporting Standard for Category 15 investment activities.

This is why we advocate a bottom-up approach to quantifying emissions instead of a top-down one. However, when many companies still lack the capabilities to track emissions, proxies are often the only way to get the job done.

One interviewee who oversees sustainability operations at a regional bank revealed:

“There’s a lack of emissions data for SMEs. So, even if they are included, a lot of times we probably use a proxy.”

At this stage, unlisted clients and SMEs are unlikely to be measuring their Scope 1 and 2 emissions and will need guidance on it. By exploring emerging tools (for example, Unravel Carbon, The Carbon Trust’s Carbon Footprint Calculator) and informing clients of the input data needed to calculate their footprint (e.g. fuel consumption per kWh) more granular and accurate data sets can be obtained, reducing the amount of time spent on desktop research and aggregating data across portfolios. It’s essential that FIs educate SMEs on the optimal tools and systems to gather and process primary data so that the data collection process can be automated.

If proxies must be used, the methodology must be documented for regulators to review during the audit, according to PCAF standards. However, regulators often scrutinise the proportion of proxies used in calculations as it makes disclosed emissions significantly less reliable.

Providing sustainability teams with the provenance of emissions data

If the sustainability team can’t verify the sources of data found during desktop research, it undermines the reliability of any financed emissions calculations that come afterwards.

One interviewee expressed a major pain point they faced regarding the reliability of data:

“We don’t know if the emissions numbers [SMEs give us] are assured because SMEs don’t need to publish reports, so if they hire an auditor to assure the numbers- that’s [an] extra cost.”

Ultimately, the centralisation of emissions data in an interoperable national database is the gold key to all the issues with sourcing and trusting data. Recognising this, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) launched Project Greenprint in late 2023, a platform that aims to simplify ESG data collection, sharing and computation. As Greenprint is being stress-tested with a group of trial users, are there other ways to automate and simplify segments of the data collection process?

Our interviewees shared some useful features they were looking for in emissions tracking platforms:

Platforms that can trace datasets to their sources for checking, and recommend which one to choose for the calculation

Platforms which can automate the process of mapping emissions into different asset classes outlined in PCAF

Seamless integration between reporting standards and decarbonisation platforms is imminent. Designing for a future where all of this is possible sets a precedent for transparent, accurate and efficient sustainability reporting.

The future roadmap

The path to net-zero emissions is shrouded with uncertainty. Many FIs rely on a mix of indicative signposts from regulatory bodies, market competitors and emerging technology to point them towards the right direction.

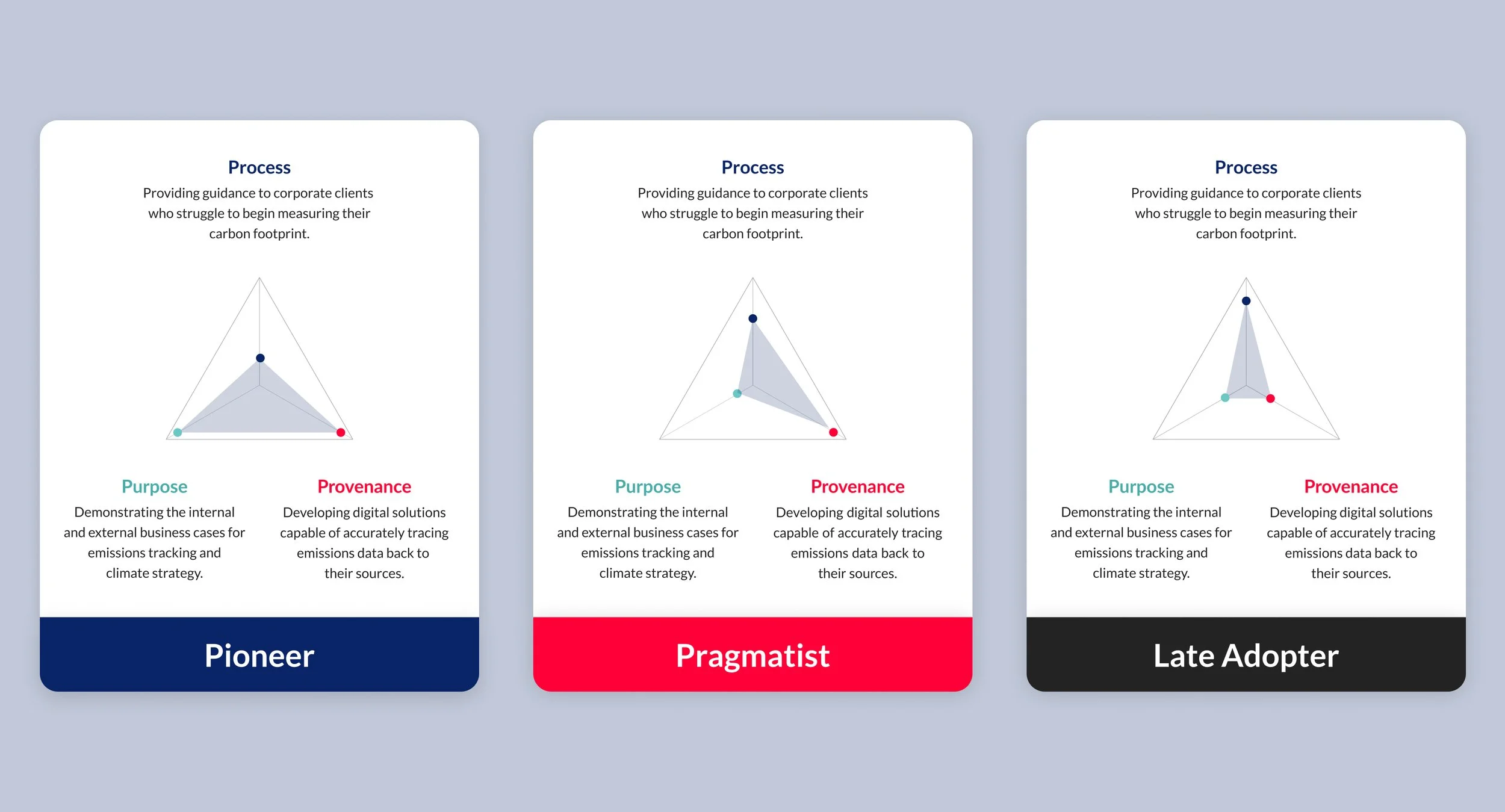

Those who are truly committed to net-zero must have the foresight to invest in the three key areas concerning people, process and provenance. Depending on their maturity level, each FI will have to prioritise areas to focus on.

Pioneers are likely to focus on higher risk, innovative solutions such as building internal capabilities for scenario modelling and portfolio emissions projections. Although they may already have established workbenches and tools in place, their in-house product teams may require design support to identify and deliver optimal platform features.

Pragmatists are more focused on optimising labour-intensive workflows through streamlining the data collection process. They will benefit from service blueprinting or journey mapping, which will help to identify opportunities to optimise business processes and reduce pain points.

Late adopters will be focused on establishing calculation methodology and convincing internal and external stakeholders to buy-in to climate initiatives. They are likely to be a small, fairly new department in the wider organisation that will benefit from stakeholder alignment on the the business value of climate management strategy. They may also require assistance in assessing the feasibility of implementation with different business teams.

Most FIs who have insufficient capacity are stuck at the perfunctory reporting stage and are unable to develop more efficient solutions for climate management. As FIs strive to be more accountable to their net-zero transition plans, they need to strategically redesign their current workflows and spark behavioural changes within the organisation.

Want a full detailed journey map?

Fill in your details to download the journey map